Computer Networks

Software Defined Networking (Part 2)

27 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Software Defined Networking (Part 2)

Revisiting the Motivation for SDN

In this topic, we are talking about the motivation that led to SDN.

As IP networks grew in adoption worldwide, there were a few challenges that became more and more pronounced, such as:

- Handling the ever growing complexity and dynamic nature of networks: The implementation of network policies required changes right down to each individual network device, which were often carried out by vendor-specific commands and required manual configurations. This was a heavy upkeep for operators. Traditional IP networks are quite far away from achieving automatic response mechanisms to dynamic network environment changes.

- Tightly coupled architecture: The traditional IP networks consist of a control plane (handles network traffic) and a data plane (forwards traffic based on the control plane's decisions) that are bundled together. They are contained inside networking devices, and are thus not flexible to work on. This is evidenced by the fact that any new protocol update takes as long as 10 years, because of the way these changes need to percolate down to every networking device that is a part of the IP network.

Software Defined Networking. This networking paradigm is an attempt to overcome limitations of the legacy IP networking paradigm. It starts by separating out the control logic (in the control plane) from the data plane. With this separation, the network switches simply perform the task of forwarding, and the control logic is purely implemented in a logically centralized controller (or a network OS), thereby making it possible for innovation to occur in areas of network reconfiguration and policy enforcement. Despite the centralized nature of control logic, in practice, production-level SDNs need a physically distributed control plane to achieve performance, reliability and scalability.

The separation of control and data plane is achieved by using a programming interface between the SDN controller and the switches. The SDN controller controls the data plane elements via the API. An example of such an API is OpenFlow. A switch in OpenFlow has one or more tables for packet handling rules. Each rule matches a subset of network traffic and performs actions such as dropping, forwarding, modifying etc. An OpenFlow switch can be instructed by the controller to behave like a firewall, switch, router, or even perform other roles like load balancer, traffic shaper, etc.

As opposed to traditional IP networks, SDN principles allow for a separation of concerns introduced between the definition of networking policies, their implementation in hardware, and the forwarding of traffic. It is this separation that allows for networking control problems to be viewed as tractable pieces, allowing for newer networking abstractions and simplifying networking management, allowing innovation.

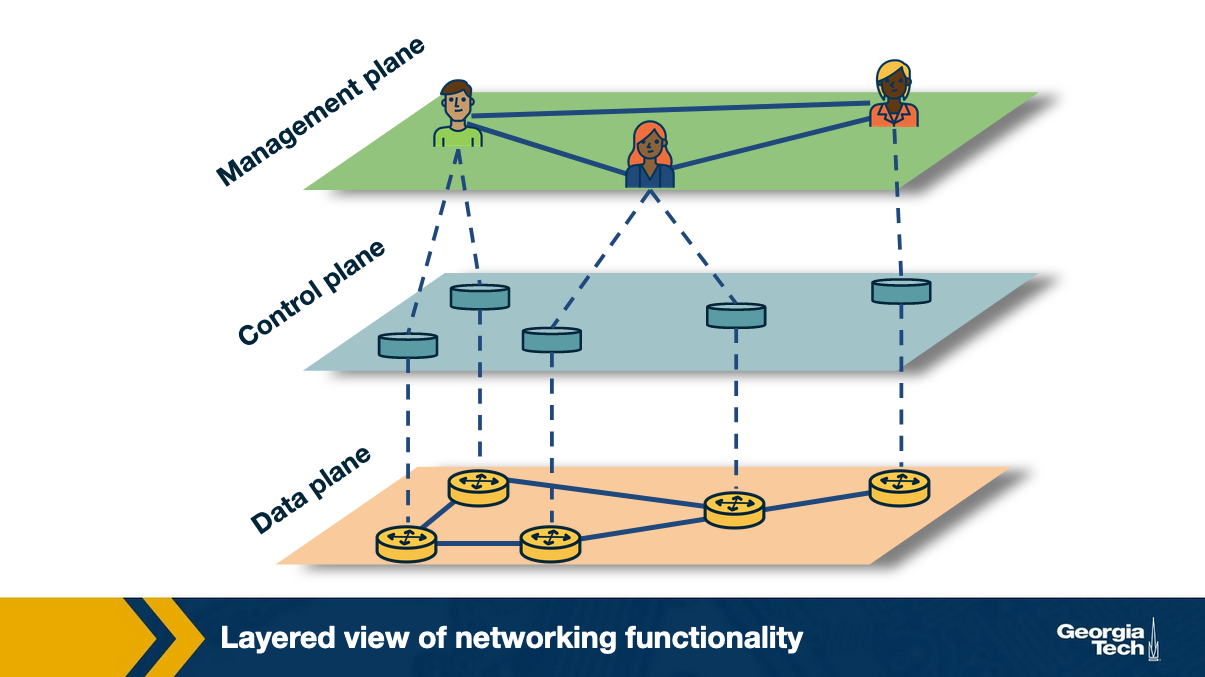

Traditionally viewed, computer networks have three planes of functionality, which are all abstract logical concepts:

Data plane: These are functions and processes that forward data in the form of packets or frames.

Control plane: These refer to functions and processes that determine which path to use by using protocols to populate forwarding tables of data plane elements.

Management plane: These are services that are used to monitor and configure the control functionality, e.g. SNMP-based tools.

In short, say if a network policy is defined in the management plane, the control plane enforces the policy and the data plane executes the policy by forwarding the data accordingly.

SDN Advantages

What are the main differences between the traditional approach (conventional networks) and the new SDN paradigm? Since the two approaches have contrasting differences, what are the advantages to using the SDN technology?

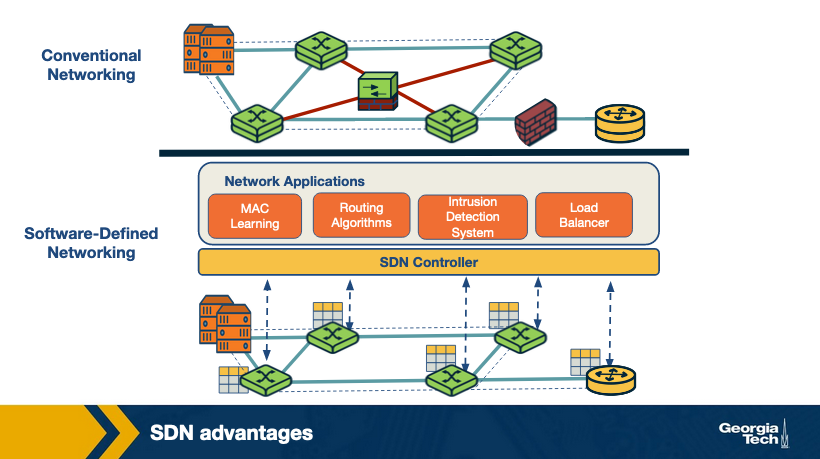

Conventional networks: We saw earlier that these networks come with a tightly coupled data and control plane, thereby making the networking components physically embedded. As a result, to add a new networking feature, one has to go through the process of modifying all control plane devices - e.g. installing new firmware / hardware upgrades. To avoid this, traditionally, a new specialized equipment was introduced (known as middlebox) through which concepts and features such as load balancers, intrusion detection systems, firewalls, etc. were introduced. Since these middleboxes are required to be carefully placed in the network topology, it is much harder to later change or reconfigure them.

Software-defined networks: Since SDN decouples the control plane from the physical networking devices, it isolates itself as an external entity (SDN controller). With this, middlebox services can be viewed as a SDN controller application. This approach has several advantages:

- Shared abstractions: These middlebox services (or network functionalities) can be programmed easily now that the abstractions provided by the control platform and network programming languages can be shared.

- Consistency of same network information: All network applications have the same global network information view, leading to consistent policy decisions while reusing control plane modules

- Locality of functionality placement: Previously, the location of middleboxes was a strategic decision and big constraint. However, in this model, the middlebox applications can take actions from anywhere in the network.

- Simpler integration: Integrations of networking applications are smoother. For example, load balancing and routing applications can be combined sequentially.

The SDN Landscape

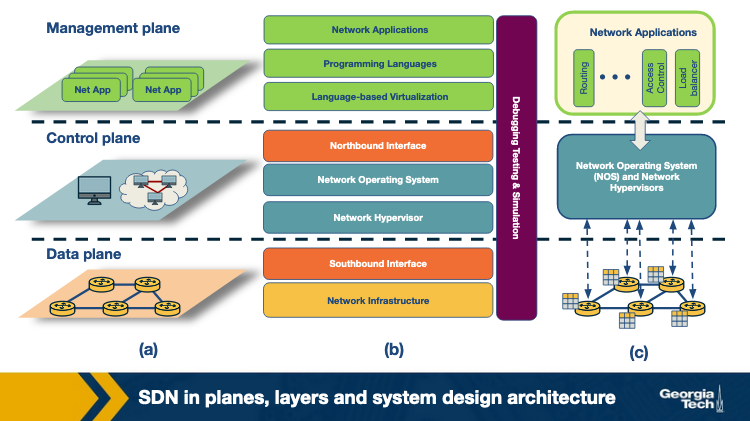

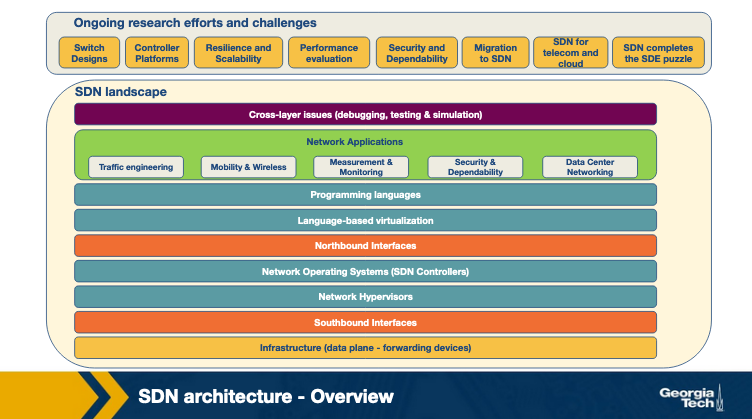

In this topic we are looking at an overview of the SDN-landscape. The landscape of the SDN architecture can be decomposed into layers as shown in the figure below.

Each layer performs its own functions through different technologies. The figure above presents three perspectives of the SDN landscape: (a) a plane-oriented view, (b) the SDN layers, and (c) a system design perspective.

Next, for each layer, we are providing an overview of the technologies that have been developed. Also, for some representative technologies we are referencing links to actively maintained tutorials.

-

Infrastructure: Similar to traditional networks, an SDN infrastructure consists of networking equipment (routers, switches and other middlebox hardware). What is now different is that these physical networking equipment are merely forwarding elements that do a simple forwarding task, and any logic to operate them is directed from the centralized control system. Popular examples of such infrastructure equipment include OpenFlow (software) switches such as SwitchLight, Open vSwitch, Pica8, etc.

- For further details and hands on tutorial please look through these links: OpenFlow: https://github.com/mininet/openflow-tutorial/wiki (Links to an external site.)

-

Southbound interfaces: These are interfaces that act as connecting bridges between connecting and forwarding elements, and since they sit in between control and data plane, they play a crucial role in separating control and data plane functionality. These APIs are tightly coupled with the forwarding elements of the underlying physical or virtual infrastructure. The most popular implementation of Southbound APIs for SDNs is OpenFlow, however there are other APIs proposed such as ForCES, OVSDB, POF, OpFlex, OpenState, etc.

- For more reading and hands on for OVSDB: http://docs.openvswitch.org/en/latest/ref/ovsdb.7/ (Links to an external site.)

- Network virtualization: For a complete virtualization of the network, the network infrastructure needs to provide support for arbitrary network topologies and addressing schemes, similar to the computing layer. Existing virtualization constructs such as VLAN, NAT and MLPS are able to provide full network virtualization, however these technologies are connected by a box-by-box basis configuration and there is no unifying abstraction that can be leveraged to configure these in a global manner, thereby making current network provisioning tasks as long as months and years. New advancements in SDN network virtualization such as VxLAN, NVGRE, FlowVisor, FlowN, NVP are promising.

-

Network operating systems: The promise of SDN is to ease network management and solve networking problems by using a logically centralized controller by way of a network operating system (NOS). The value of a NOS is in providing abstractions, essential services and common APIs to developers. For example, while programming a network policy, if a developer doesn't need to worry about low-level details about data distribution among routing elements, that is an abstraction. Such systems propel more innovation by reducing inherent complexity of creating new network protocols and network applications. Some popular NOSs are OpenDayLight, OpenContrail, Onix, Beacon and HP VAN SDN.

- For more details and tutorials for OpenDayLight, please follow this link: https://www.opendaylight.org/technical-community/getting-started-for-developers/tutorials (Links to an external site.)

-

Northbound interfaces: The two core abstractions of an SDN ecosystem are the Southbound and Northbound interfaces. We have already seen Southbound interfaces, and that it already has a widely acceptable norm (OpenFlow). Compared to that, a standard for Northbound interface is still an open problem, as are its use cases. What is relatively clear is that Northbound interfaces are supposed to be a mostly software ecosystem, as opposed to the Southbound interfaces. Another key requirement is the abstraction that guarantees programming language and controller independence. Some popular examples are Floodlight, Trema, NOX, Onix and SFNet.

- For a tutorial to get a more hands on experience on Floodlight: https://floodlight.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/floodlightcontroller/pages/1343514/Tutorials (Links to an external site.)

- Language-based virtualization: An important characteristic of virtualization is the ability to express modularity and allowing different levels of abstraction. For example, using virtualization we can view a single physical device in different ways. This takes away the complexity away from application developers without compromising on security which is inherently guaranteed. Some popular examples of programming languages that support virtualization are Pyretic, libNetVirt, AutoSlice, RadioVisor, OpenVirteX, etc.

-

Network programming languages: Network programmability can be achieved using low-level or high-level programming languages. Using low-level languages, it is difficult to write modular code, reuse it and it generally leads to more error-prone development. High level programming languages in SDNs provide abstractions, make development more modular, code more reusable in control plane, do away with device specific and low-level configurations, and generally allow faster development. Some examples of network programming languages in SDNs are Pyretic, Frenetic, Merlin, Nettle, Procera, FML, etc.

- For a tutorial on Frenetic programming language: http://frenetic-lang.github.io/tutorials/Introduction/ (Links to an external site.) Pyretic: https://github.com/frenetic-lang/pyretic/wiki (Links to an external site.)

- Network applications: These are the functionalities that implement the control plane logic and translate to commands in the data plane. SDNs can be deployed on traditional networks, and can find itself in home area networks, data centers, IXPs etc. Due to this, there is a wide variety of network applications such as routing, load balancing, security enforcement, end-to-end QoS enforcement, power consumption reduction, network virtualization, mobility management, etc. Some well known solutions are Hedera, Aster*x, OSP, OpenQoS, Pronto, Plug-N-Serve, SIMPLE, FAMS, FlowSense, OpenTCP, NetGraph, FortNOX, FlowNAC, VAVE, etc.

SDN Infrastructure Layer

In the previous topic, we talked about the landscape of an SDN infrastructure. In this topic we are zooming into the infrastructure layer.

The SDN infrastructure composes of networking equipment (routers, switches and appliance hardware) performing simple forwarding tasks. The physical devices do not have embedded intelligence or control, as the network intelligence is now delegated to a logically centralized control system - the Network Operating System (NOS). An important difference in these networks is that they are built on top of open and standard interfaces that ensure configuration and communication compatibility and interoperability among different control plane and data plane devices. As opposed to traditional networks that use proprietary and closed interfaces, these networks are able to dynamically program heterogeneous network devices as forwarding devices.

In the SDN architecture, a data plane device is a hardware or software entity that forwards packets, while a controller is a software stack running on commodity hardware. A model derived from OpenFlow is currently the most widely accepted design of SDN data plane devices. It is based on a pipeline of flow tables where each entry of a flow table has three parts: a) a matching rule, b) actions to be executed on matching packets, and c) counters that keep statistics of matching packets. Other SDN-enabled forwarding device specifications include Protocol-Oblivious Forwarding (POF) and Negotiable Datapath Models (NDMs).

In an OpenFlow device, when a packet arrives, the lookup process starts in the first table and ends either with a match in one of the tables of the pipeline or with a miss (when no rule is found for that packet). Some possible actions for the packet include:

- Forward the packet to outgoing port

- Encapsulate the packet and forward it to controller

- Drop the packet

- Send the packet to normal processing pipeline

- Send the packet to next flow table

SDN Southbound Interfaces

In the previous topic, we talked about the landscape of an SDN infrastructure. In this topic we are zooming into the Southbound Interfaces.

The Southbound interfaces or APIs are the separating medium between the control plane and data plane functionality.

From a legacy standpoint, development of a new switch typically takes up to two years for commercialization. Added to that is the upgrade cycles and time required to software development for the new product. Since the southbound APIs represent one of the major barriers for introduction and acceptance of any new networking technology, API proposals like OpenFlow have received good reception. These standards promote interoperability and deployment of vendor-agnostic devices. This has already been achieved by the OpenFlow-enabled equipments from different vendors.

Currently , OpenFlow is the most widely accepted southbound standard for SDNs. It provides specification to implement OpenFlow-enabled forwarding devices, and for the communication channel between data and control plane devices. There are three information sources provided by OpenFlow protocol:

- Event-based messages that are sent by forwarding devices to controller when there is a link or port change

- Flow statistics are generated by forwarding devices and collected by controller

- Packet messages are sent by forwarding devices to controller when they do not know what to do with a new incoming flow

These three channels are key to provide flow-level info to the Network Operating System (NOS).

Despite OpenFlow being the most popular southbound interface for SDN, there are others API proposals such as ForCES, OVSDB, POF, OpFlex, OpenState, etc. In case of ForCES, it provides a more flexible approach to traditional network management without changing the current architecture of the network, i.e, it does not need a logically centralized controller. The control and data planes are separated but potentially can also be kept in the same network element. OVSDB is another southbound API that acts complementary to OpenFlow or Open vSwitch. It allows the control elements to create multiple vSwitch instances, set QoS policies on interfaces, attach interfaces to the switches, configure tunnel interfaces on the OpenFlow data paths, manage queues and collect statistics.

SDN Controllers: Centralized vs Distributed

As we've seen earlier, the biggest drawback of traditional networks is that they are configured using low-level, device-specific instruction sets and run mostly proprietary network operating systems. This challenges the notion of device-agnostic developments and abstraction, which are key ideas to solve networking problems. SDN offers these by means of a logically centralized control. A controller is a critical element in an SDN architecture as it is the key supporting piece for control logic (applications) to generate network configuration based on the policies defined by the network operator. There is a broad range of architectural choices when it comes to controllers and control platforms.

Core controller functions

Some base network service functions are what we consider the essential functionality all controllers should provide. Functions such as topology, statistics, notifications, device management, along with shortest path forwarding and security mechanisms are essentials network control functionalities that network applications may use in building its logic. For example, security mechanisms are critical components to provide basic isolation and security enforcements between services and applications. For instance, high priority services' rules should always take precedence over rules created by applications with low priority.

SDN Controllers can be categorized based on many aspects. In this topic we will categorize them based on centralized or distributed architecture.

Centralized controllers

In this architecture, we typically see a single entity that manages all forwarding devices in the network, which is a single point of failure and may have scaling issues. Also, a single controller may not be enough to handle a large number of data plane elements. Some enterprise class networks and data centers use such architectures, such as Maestro, Beacon, NOX-MT. They use multi-threaded designs to explore parallelism of multi-core computer architectures. For example, Beacon can deal with more than 12 million flows per second by using large sized computing nodes of cloud providers. Other single controller architectures such as Trema, Ryu NOS, etc. target specific environments such as data centers, cloud infras. Controllers such as Rosemary offer specific functionality and guarantees security and isolation of applications by using a container based architecture called micro-NOS.

Distributed controllers

Unlike single controller architectures that cannot scale in practice, a distributed network operating system (controller) can be scaled to meet the requirements of potentially any environment - small or large networks. Distribution can occur in two ways: it can be a centralized cluster of nodes or physically distributed set of elements. Typically, a cloud provider that runs across multiple data centers interconnected by a WAN may require a hybrid approach to distribution - clusters of controllers inside each data center and distributed controller nodes in different sites. Properties of distributed controllers:

- Weak consistency semantics

- Fault tolerance

An example Controller: ONOS

As we saw in the previous topic there are different types of SDN controllers. In this topic, we are talking about an example distributed controller.

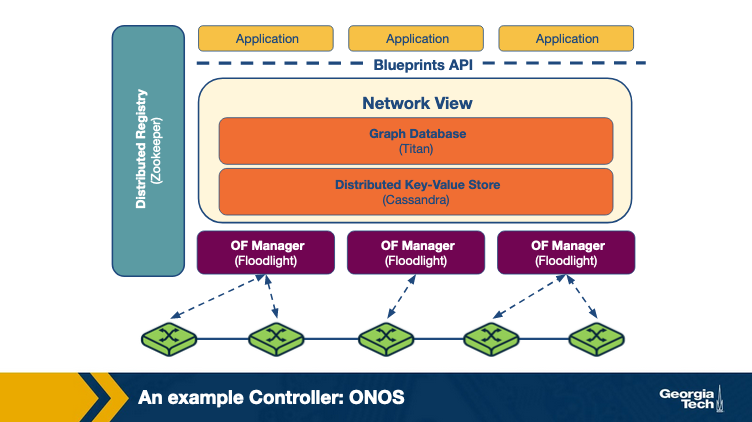

ONOS (Open Networking Operating System) is a distributed SDN control platform. It aims to provide a global view of the network to the applications, scale-out performance and fault tolerance. The prototype was built based on Floodlight, an open-source single-instance SDN controller. The below figure depicts the high level architecture.

Owing to the distributed architecture of ONOS, there are several ONOS instances running in a cluster. The management and sharing of the network state across these instances is achieved by maintaining a global network view. This view is built by using the network topology and state information (port, link and host information, etc) that is discovered by each instance.

To make forwarding and policy decisions, the applications consume information from the view and then update these decisions back to the view. The corresponding OpenFlow managers receive the changes the applications make to the view, and the appropriate switches are programmed.

Titan, a graph database and a distributed key value store Cassandra is used to implement the view. The applications interact with the network view using the Blueprints graph API.

The distributed architecture of ONOS offers scale-out performance and fault tolerance. Each ONOS instance serves as the master OpenFlow controller for a group of switches. The propagation of state changes between a switch and the network view is handled solely by the master instance of that switch. The workload can be distributed by adding more instances to the ONOS cluster in case the data plane increases in capacity or the demand in the control plane goes up.

To achieve fault tolerance, ONOS redistributes the work of a failed instance to other remaining instances. Each switch in the network connects to multiple ONOS instances with only one instance acting as its master. Each ONOS instance acts as a master for a subset of switches. Upon failure of an ONOS instance, an election is held on a consensus basis to choose a master for each of the switches that were controlled by the failed instance. For each switch, a master is selected among the remaining instances with which the switch had established connection. At the end of election for all switches, each switch would have at most one new master instance.

Zoopkeeper is used to maintain the mastership between the switch and the controller.

Programming the Data Plane: The Motivation

In this topic, we are talking about the need to offer programmability on the data plane and we are introducing P4 which is a language that was developed for this purpose.

P4 (Programming Protocol-independent Packet Processors) is a high-level programming language to configure switches which works in conjunction with SDN control protocols. The popular vendor-agnostic OpenFlow interface, which enables the control plane to manage devices from different vendors, started with a simple rule table to match packets based on a dozen header fields. However, this specification has grown over the years to include multiple stages of the rule tables with increasing number of header fields to allow better exposure of a switch's functionalities to the controller.

Thus, to manage the demand for increasing number of header fields, a need arises for an extensible, flexible approach to parse packets and match header fields while also exposing an open interface to the controllers to leverage these capabilities.

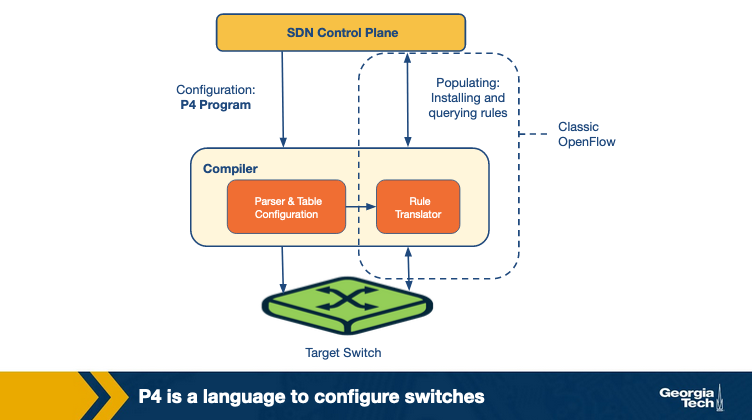

P4 is used to configure the switch programmatically and acts as a general interface between the switches and the controller with its main aim of allowing the controller to define how the switches operate. The below figure explains the relationship between P4 and existing APIs such as OpenFlow, which targets to populate forwarding rules in fixed function switches:

The following are the primary goals of P4:

- Reconfigurability: The way parsing and processing of packets takes place in the switches should be modifiable by the controller.

- Protocol independence: To enable the switches to be independent of any particular protocol, the controller defines a packet parser and a set of tables mapping matches and their actions. The packet parser extracts the header fields which are then passed on to the match+action tables to be processed.

- Target independence: The packet processing programs should be programmed independent of the underlying target devices. These generalized programs written in P4 should be converted into target-dependent programs by a compiler which are then used to configure the switch.

Programming the Data Plane: P4's Forwarding Model

In this topic, we are talking in more detail about P4 and the forwarding model that this approach proposes.

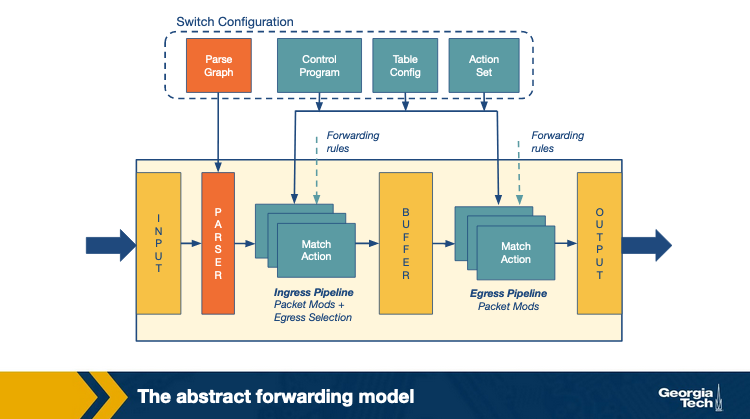

The switches using P4 use a programmable parser and a set of match+action tables to forward packets. The tables can be accessed in multiple stages in a series or parallel manner. This contrasts with OpenFlow, which supports only fixed parsers based on predetermined header fields and only a series combination of match+actions tables.

The P4 model allows generalization of packet processing across various forwarding devices such as routers, load balancers, etc., using multiple technologies such as fixed function switches, NPUs, etc.. This generalization allows the design of a common language to write packet processing programs that are independent of the underlying devices. A compiler then maps these programs to different forwarding devices.

The following are the two main operations of the P4 forwarding model:

- Configure: These sets of operations are used to program the parser. They specify the header fields to be processed in each match+action stage and also define the order of these stages.

- Populate: The entries in the match+action tables specified during configuration may be altered using the populate operations. It allows addition and deletion of the entries in the tables.

In short, configuration determines the packet processing and the supported protocols in a switch whereas population decides the policies to be applied to the packets.

An Introduction To The P4 Programming Language

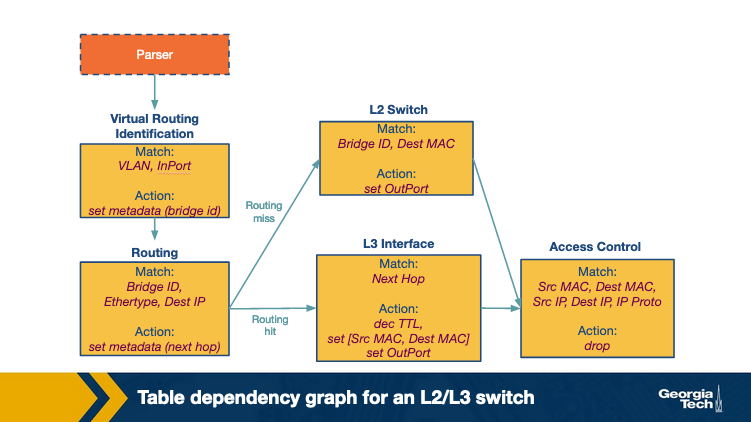

The abstract forwarding model we saw in the earlier section is used to define a programming language that defines the configuration of a switch and the processing of a packet. P4 is one such packet processing language with the following characteristics:

- Legal header types are declared to let the parser be aware of the possible packet formats. For example, the format of an IPv4 header may be specified with the list of headers allowed to follow an IP header.

- A control flow program which uses the declared header types and a set of actions to specify how the headers are processed. For example, checksums may be computed or new tunnel headers may be added.

- Table Dependency Graphs (TDGs) are used to identify the dependencies between the header fields and help determine the order in which the tables can be executed. Tables with no dependencies may be executed in parallel. Each node in the TDG maps to a match+action table. The nodes contain the match and action with the control flow between tables acting as the edges between the nodes. The analysis of dependencies between the nodes determine where a table may be placed in the pipeline. However, these graphs are not readily available to the programmer.

To address the dependency issues, the control flow logic to process packets is written using P4 which is then translated to TDGs using a compiler for dependency analysis. The compiler then maps the TDG to a specific target switch.

SDN Applications: Overview

In this topic we are looking at an overview of the application areas of SDN.

Traffic Engineering

This is one of the major areas of interest for SDN applications with main focus on optimizing the traffic flow so as to minimize power consumption, judiciously use network resources, perform load balancing, etc. With the help of optimization algorithms and monitoring the data plane load via southbound interfaces, the power consumption can be reduced drastically while still maintaining the desired goals of performance. ElasticTree is one such application which identifies and shut downs specific links and devices depending on the traffic load. Load balancing applications such as Plug-n-Serve and Aster*x achieve scalability by creating rules based on wildcard patterns which enables handling of large numbers of requests from a particular group. Another use case of SDN applications is to automate the management of router configuration to reduce the growth in routing tables due to duplication of data. Large scale service providers also use SDN for traffic optimization to scale dynamically, e.g. ALTO VPN enables dynamic provisioning of VPNs in cloud infrastructure.

Mobility and Wireless

The existing wireless networks face various challenges in its control plane including management of the limited spectrum, allocation of radio resources and load-balancing. The deployment and management of various wireless networks (WLANS, cellular networks) is made easier using SDN. SDN-based wireless networks offer a variety of features including on-demand virtual access points (VAPs), usage of spectrum dynamically, sharing of wireless infrastructure, etc. OpenRadio, which is considered as the OpenFlow for wireless, enables decoupling of the wireless protocols from the underlying hardware by providing an abstraction layer. Light virtual access points (LVAPs) offer an improved way of managing wireless networks by using a one-to-one mapping between LVAPs and clients. The Odin framework leverages LVAPs and the applications built on it provide features such as mobility management, channel selection algorithms, etc. In contrast to traditional wireless networks, a user can move between APs without any visible lag as the mobility manager can automatically move the client LVAP to a different AP.

Measurement and Monitoring

The first class of applications in this domain aims to add features to other networking services. For example, new functions can be added easily to measurement systems such as BISmark in an SDN-based broadband connection, which enables the system to respond to change in network conditions. A second class of these applications aim to improve the existing features of SDNs using OpenFlow such as reducing the load on the control plane arising from collection of data plane statistics using various sampling and estimation techniques. OpenSketch is a southbound API that offers flexibility for network measurements. OpenSample and PayLess are examples of monitoring frameworks.

Security and Dependability

The applications in this area focus majorly on improving the security of networks. One approach of using SDN to enhance security is to impose security policies on the entry point to the network. Another approach is to use programmable devices to enforce security policies on a wider network. DDoS detection, an SDN application identifies and mitigates DDoS flooding attacks by leveraging the timely information collected from the network. Furthermore, SDN has also been used to detect any anomalies in the traffic, to randomly mutate the IP addresses of hosts to fake dynamic IPs to the attackers (OF-RHM) , and monitoring the cloud infrastructures (CloudWatcher).

With regards to improving the security of SDN itself, there have been simple approaches like rule prioritizations for applications. However, there's still significant room for research and improvement in this area.

Data Center Networking

Data Center networking can be revolutionized by the use of SDN which aims to offer services such as live migration of networks, troubleshooting, real-time monitoring of networks among various other features. SDN applications can also help detect anomalous behavior in data centers by defining different models and building application signatures from observing the information collected from network devices in the data center. Any deviation from the signature history can be identified and appropriate measures can be taken. SDN also helps in performing dynamic reconfigurations of virtual networks involved in a live virtual network migration, which is an important feature of virtual networks in cloud. LIME is one such SDN application which aims to provide live migration and FlowDiff is an application which detects abnormalities.

SDN Application Example: A Software Defined Internet Exchange

In a previous topic, we talked about the Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and their importance in today's Internet ecosystem. In this topic we are looking at how the SDN technology could be applied to improve the operation of an IXP. The SDN technology has many applications. In this topic we are only looking into an example SDN application for IXPs.

The routing of packets across the Internet is currently handled through the popular Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). However, BGP has limitations which makes Internet routing unreliable and difficult to manage. The main limitations are:

- Routing only on destination IP prefix - The routing is decided based on the destination prefix IP of the incoming packet. There's no flexibility to customize rules for example based on the traffic application or the source/destination network.

- Networks have little control over end-to-end paths - Networks can only select paths advertised by direct neighbors. Networks cannot directly control preferred paths but instead have to rely on indirect mechanisms such as “AS Path prepending”.

Using SDN, researchers have proposed to address the above BGP limitations. SDN can perform multiple actions on the traffic by matching over various header fields, not only by matching on the destination prefix.

We have talked about IXPs at previous lecture, but as a reminder, an Internet Exchange Point (IXP) is a physical location that facilitates interconnection between networks so that they can exchange traffic and BGP routes. In the context of the IXPs, researchers have proposed an SDN based architecture, called SDX.

SDX was proposed to implement multiple applications including:

- Application specific peering - Custom peering rules can be installed for certain applications, such as high-bandwidth video applications like Netflix or YouTube which constitute a significant amount of traffic volume.

- Traffic engineering - Controlling the inbound traffic based on source IP or port numbers by setting forwarding rules.

- Traffic load balancing - The destination IP address can be rewritten based on any field in the packet header to balance the load.

- Traffic redirection through middleboxes - Targeted subsets of traffic can be redirected to middleboxes.

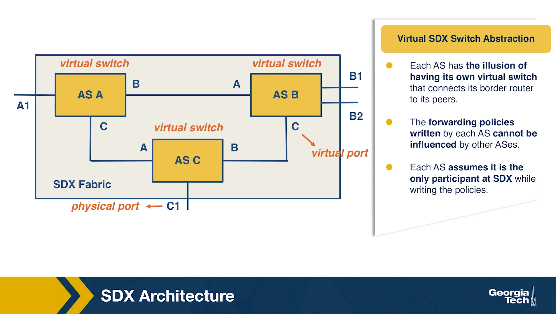

SDX Architecture

Let's look into the proposed SDX architecture.

In a traditional IXP the participant ASes connect their BGP-speaking border router to a shared layer-two network and a BGP route server. The layer-2 network is used for forwarding packets (data plane) and the BGP route server is used for exchanging routing information (control plane).

In the SDX architecture, each AS the illusion of its own virtual SDN switch that connects its border router to every other participant AS. For example, AS A has a virtual switch connecting to the virtual switches of ASes B and C.

Each AS can define forwarding policies as if it is the only participant at the SDX, without influencing how other participants forward packets on their own virtual switches. Each AS can have its own SDN applications for dropping, modifying, or forwarding their traffic. The policies can also be different based on the direction of the traffic (inbound or outbound). An inbound policy is applied on the traffic coming from other SDX participant on a virtual switch. An outbound policy is applied to traffic from the participant's virtual switch port towards other participants. The SDX is responsible to combine the policies from multiple participants into a single policy for the physical switch.

To write policies SDX uses the Pyretic language to match header fields of the packets and to express actions on the packets.

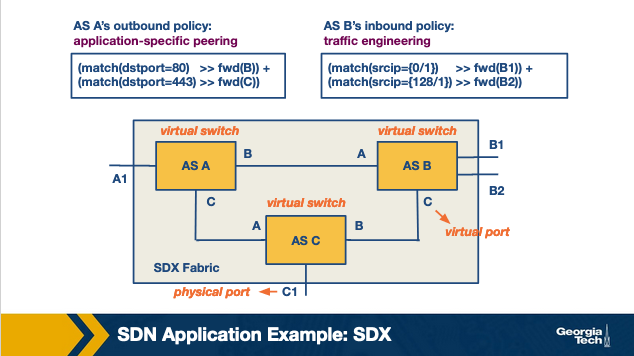

Let's consider the example of application-specific peering, and let's see how a participant network expresses example policies:

According to AS A's outbound policy, the HTTP traffic with destination port 80 is forwarded to AS B and HTTPS traffic with destination port 443 is forwarded to AS C.

This is expressed using the match statement:

(match(dstport = 80) >> fwd(B)) + (match(dstport = 443) >> fwd(C))

- The match statement filters and return the packets that match the specified port numbers.

- The sequential operator “>>” then forwards the returned packets to the next function.

- The fwd() function modifies the location (next destination) of the packet to the location of the corresponding switch.

- The parallel operator “+” applies each given policy to the packets and returns the combined output. If neither of the two policies matches, the packet is dropped.

SDN Applications: Wide Area Traffic Delivery

In this section, we'll look at a few applications of SDN, specifically SDX, in the domain of wide area traffic delivery.

Application specific peering

ISPs prefer dedicated ASes to handle the high volume of traffic flowing from high bandwidth applications such as YouTube, Netflix. This can be achieved by identifying a particular application's traffic using packet classifiers and directing the traffic in a different path. However this involves configuring additional and appropriate rules in the edge routers of the ISP. This overhead can be eliminated by configuring custom rules for flows matching a certain criteria at the SDX.

Inbound traffic engineering

An SDN enabled switch can be installed with forwarding rules based on the source IP address and source port of the packets, thereby enabling an AS to control how the traffic enters its network. This is in contrast with BGP which performs routing based solely on the destination address of a packet. Although there are workarounds such as using AS path prepending and selective advertisements to control the inbound traffic using BGP, they come with certain limitations. An AS's local preference takes a higher priority for the outgoing traffic and the selective advertisements can lead to pollution of the global routing tables.

Wide-area server load balancing

The existing approach of load balancing across multiple servers of a service involves a client's local DNS server issuing a request to the service's DNS server. As a response, the service DNS returns the IP address of a server such that it balances the load in its system. This involves DNS caching which can lead to slower responses in case of a failure. A more efficient approach to load balancing can be achieved with the help of SDX, as it supports modification of the packet headers. A single anycast IP can be assigned to a service, and the destination IP addresses of packets can be modified at the exchange point to the desired backend server based on the request load.

Redirection through middle boxes

SDX can be used to address the challenges in existing approaches to using middleboxes (firewalls, load balancers, etc). The placement of middleboxes are usually targeted at important junctions, such as the boundary of the enterprise networks with their upstream ISPs. To avoid the high expenses involved in placing middleboxes at every location in case of geographically large ISPs, the traffic is directed through a fixed set of middleboxes by the ISPs. This is done by manipulating routing protocols such as internal BGP to essentially hijack a subset of traffic and sending it to a middlebox. This approach could result in unnecessary additional traffic being redirected, and is also limited by the fixed set of middleboxes. To overcome these issues, an SDX can identify and redirect the desired traffic through a sequence of middleboxes.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy