Databases

SQL

14 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

SQL

SQL Introduction

SQL is the lingua franca of databases, or as Mike Stonebraker called it, the intergalactic data speak. Most databases support some form of SQL, and most data sit in relational databases accessed through SQL. Although we use XML frequently to describe interfaces and exchange data, the vast majority of data still sits in the SQL databases.

SQL History

SEQUEL, or Structured English QUEry Language, was the original name for SQL. SEQUEL - created by Donald Chamberlin and Raymond Boyce - was part of a research relational database prototype released by IBM in 1973 called System R. SEQUEL was later changed to SQL, or Structured Query Language. SQL is based on relational tuple calculus primarily with some foundation in relational algebra.

There are both ANSI and ISO standards for SQL. The first version of SQL was standardized in 1986, with a revision in 1989. SQL2 came later in 1992, and SQL3 was published in 1999. There have been several revisions since the release of SQL3: in 2003, 2006, 2008, and 2011, for example. Most revisions did not change the core SQL standard but added new functionality for features like temporal and spatial queries, among others.

Many database products implement the SQL standard completely or partially, including IBM Db2 (a commercial version of SYSTEM R), Oracle, Sybase, SQLServer, MySQL, and many more.

Insert

Let's look at an example of insertion. The following statement inserts a tuple

into UserInterests that has a value of 'user12@gt.edu' for Email, 'Reading'

for Interest, and 5 for SinceAge:

INSERT INTO UserInterests(Email, Interest, SinceAge)

VALUES ('user12@gt.edu', 'Reading', 5)This method of insertion only adds a single row at a time into the database. We can augment an insertion statement with a query selection on the database to insert the result of such a selection - zero or more tuples - into a table.

Delete

Let's see an example of a delete operation. Whereas the insertion statement we

saw earlier only inserts one tuple into the table, deletion can delete a set of

rows in the table. The following query deletes all tuples from UserInterests

where Interest is 'Swimming':

DELETE FROM UserInterests

WHERE Interest = 'Swimming';Update

Let's look at an update. Similar to deletions, update operations may impact a

set of tuples. The following statement sets the Interest to 'Rock Music' for

every tuple in UserInterests where Email is 'user3@gt.edu' and Interest is

'Music':

UPDATE UserInterests

SET Interest = 'Rock Music'

WHERE Email = 'user3@gt.edu'

AND Interest = 'Music';General SQL Query Syntax

Generally, we select a list of columns from a collection of tables where some condition evaluates to true. With a few exceptions, all SQL queries take the following shape:

SELECT column_1, column_2, ..., column_n

FROM table_1, table_2, ..., table_m

WHERE condition;The columns above refer to the names of database columns, such as BirthYear,

in our database tables. The tables refer to names of database tables, such as

RegularUser. The condition consists of comparisons between columns and either

constants or other columns. For example we might look for rows where `BirthYear

1985

orCurrentCity = HomeTown`. We combine conditions using nesting, conjunction, disjunction, or negation, just as we did in relational calculus and algebra.

When discussing commercial relational databases, as opposed to algebra and calculus, we use the terms column, table, and row, instead of attribute, relation, and tuple, respectively. The SQL query shown above is equivalent to the following algebra expression:

In the expression above, we take the Cartesian product of the relations of

interest. Then we select the tuples that evaluate to true for our expression.

Finally, we project the result onto the attributes of interest. We can remove

the selection operation from the algebra expression if the SQL query has no

WHERE clause.

Selection - Wildcard

The following query selects all rows from the RegularUser table:

SELECT Email, BirthYear, Sex, CurrentCity, HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;Notice that there is no WHERE clause in this expression. Also, notice that we

are explicitly enumerating all columns from RegularUser. We have this

shorthand available when selecting all columns:

SELECT *

FROM RegularUser;Selection - Where Clause

The following query selects all columns for all rows from RegularUser where

HomeTown equals 'Atlanta':

SELECT *

FROM RegularUser

WHERE HomeTown = 'Atlanta';Selection - Composite Where Clause

The following query selects all columns for all rows from RegularUser where

CurrentCity equals HomeTown or HomeTown equals 'Atlanta':

SELECT *

FROM RegularUser

WHERE CurrentCity = HomeTown OR

HomeTown = 'Atlanta';Projection

Let's say we only need information from some of the columns of the RegularUser

table - namely, Email, BirthYear, and Sex - for all users who live in

Atlanta. We can express this query as such:

SELECT Email, BirthYear, Sex

FROM RegularUser

WHERE HomeTown = 'Atlanta';The resulting table has the columns specified in the query in the same order in which we enumerated them.

Distinct

When we looked at relational algebra and calculus, we emphasized that relations are sets and that the result of a query is always a relation and, therefore, a set. In SQL, tables may have duplicate rows. Suppose we want to find the sex of all regular users in Atlanta. We can express that query as:

SELECT Sex

FROM RegularUser

WHERE HomeTown = 'Atlanta'If we have multiple rows in RegularUser with the same value of Sex, we will

have duplicate rows in our resulting one-column table. We can avoid such

duplication with the DISTINCT keyword:

SELECT DISTINCT(Sex)

FROM RegularUser

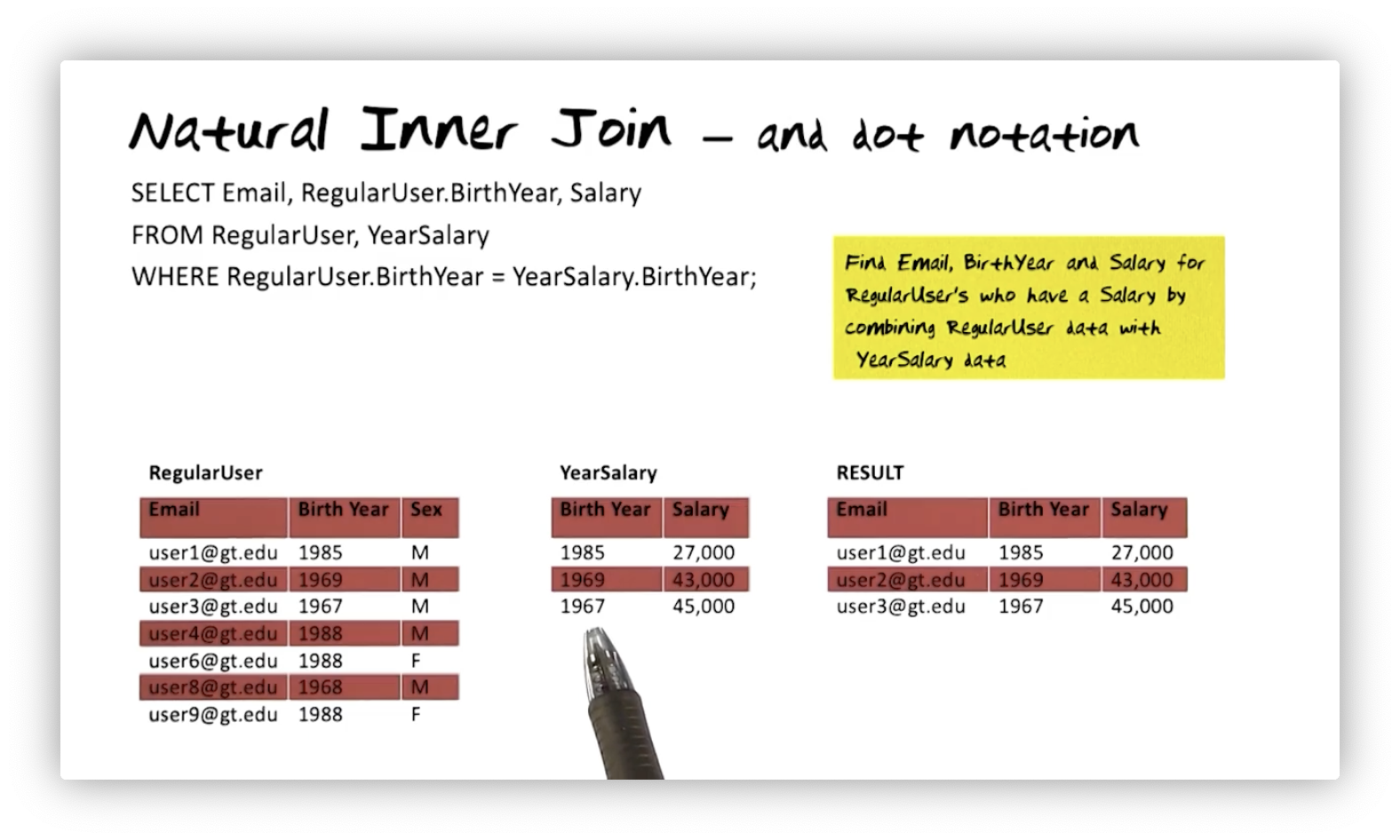

WHERE HomeTown = 'Atlanta';Natural Inner Join - Dot Notation

Suppose we want to find the email, birth year, and salary for regular users who

have a salary by joining the RegularUser table and the YearSalary table, the

latter of which has BirthYear and Salary columns. The appropriate SQL query

looks as follows:

SELECT Email, RegularUser.BirthYear, Salary

FROM RegularUser, YearSalary

WHERE RegularUser.BirthYear = YearSalary.BirthYear;Notice that our result does not have information about the last four users as

their birth year is not present in YearSalary.

When there is no ambiguity about which columns come from which tables, as is the

case for Email and Salary above, we can reference the columns without

specifying the table. Since BirthYear appears in both tables, we use dot

notation to clarify which column we are referencing. RegularUser.BirthYear

is not ambiguous, whereas BirthYear is.

In relational algebra, we didn't have to specify the join condition when the

attribute names were the same. In SQL, we must specify this condition:

RegularUser.BirthYear = YearSalary.BirthYear. However, when the column names

are the same, we also have an alternative syntax available to us:

SELECT Email, RegularUser.BirthYear, Salary

FROM RegularUser NATURAL JOIN YearSalary;If constituent tables share no columns of the same name, the natural join operation defaults to the Cartesian product.

Natural Inner Join - Aliases

As before, suppose we want to find the email, birth year, and salary for regular

users who have a salary by joining the RegularUser table and the YearSalary

table, the latter of which has BirthYear and Salary columns. We can use

aliases to rewrite this query as follows:

SELECT Email, R.BirthYear, Salary

FROM RegularUser AS R, YearSalary AS Y

WHERE R.BirthYear = Y.BirthYear;When we discussed tuple calculus, we encountered the concept of tuple variables;

R and Y are exactly tuple variables. For the scope of this query, we alias

the RegularUser and YearSalary tables as R and Y, respectively, and we

can reference these tables using their aliases anywhere in the query. When we

use R or S to range over RegularUser or YearSalary, we can imagine the

alias taking on the value of each row of the corresponding table in turn during

the query evaluation.

SQL queries can become quite large and complex, and we can use aliases to save on typing. We also use aliases to disambiguate table references; in particular, we must use aliases when joining a table with itself to distinguish between the first and second instances of the table in the join.

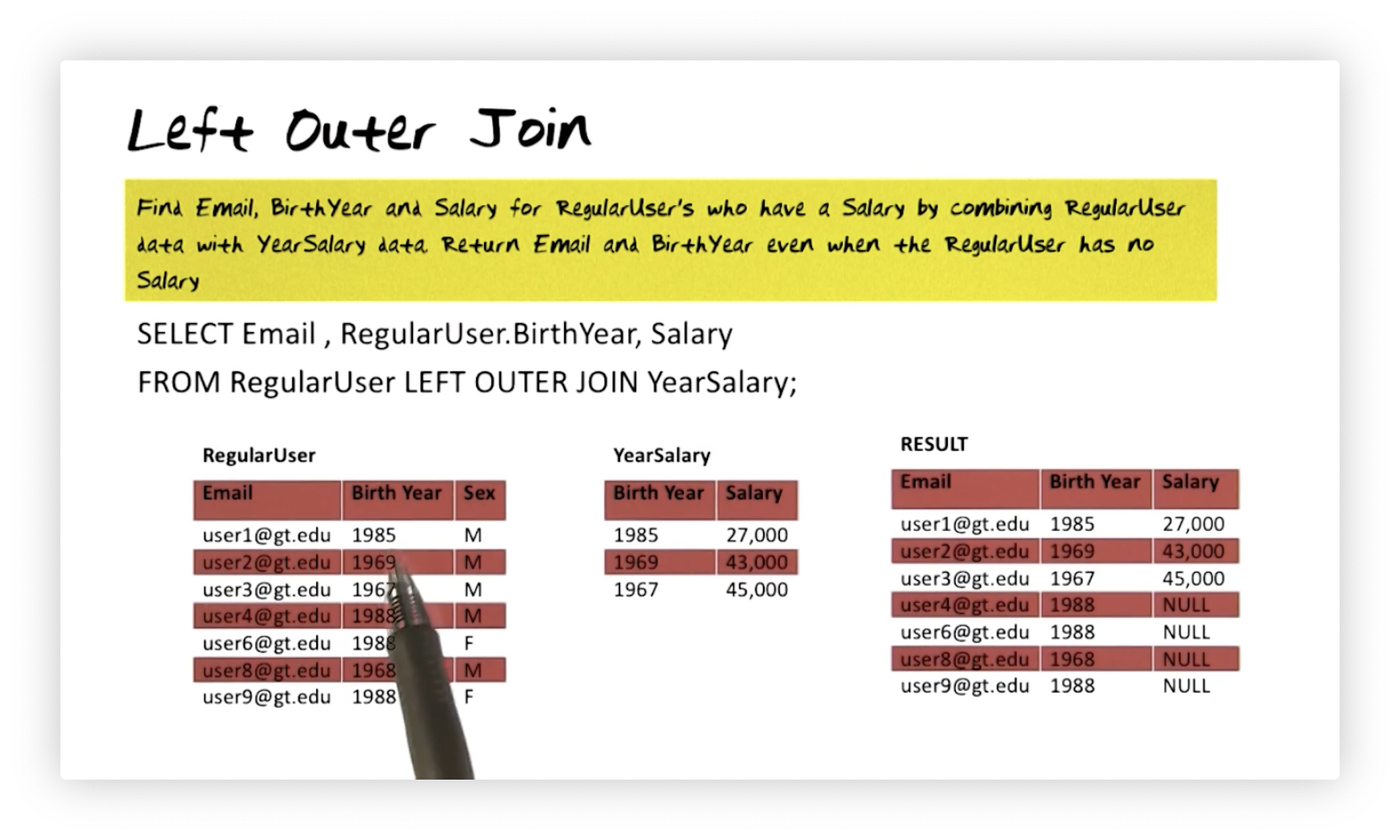

Left Outer Join

Suppose we want to find the email, birth year, and salary for regular users who

have a salary by joining the RegularUser table and the YearSalary table. We

also want to include regular users who have no salary in the result. We can

express this query as follows:

SELECT Email, RegularUser.BirthYear, Salary

FROM RegularUser LEFT OUTER JOIN YearSalary;

In this example, users who do not have associated salary information are

included in the result but have NULL values for the Salary column in the

resulting table.

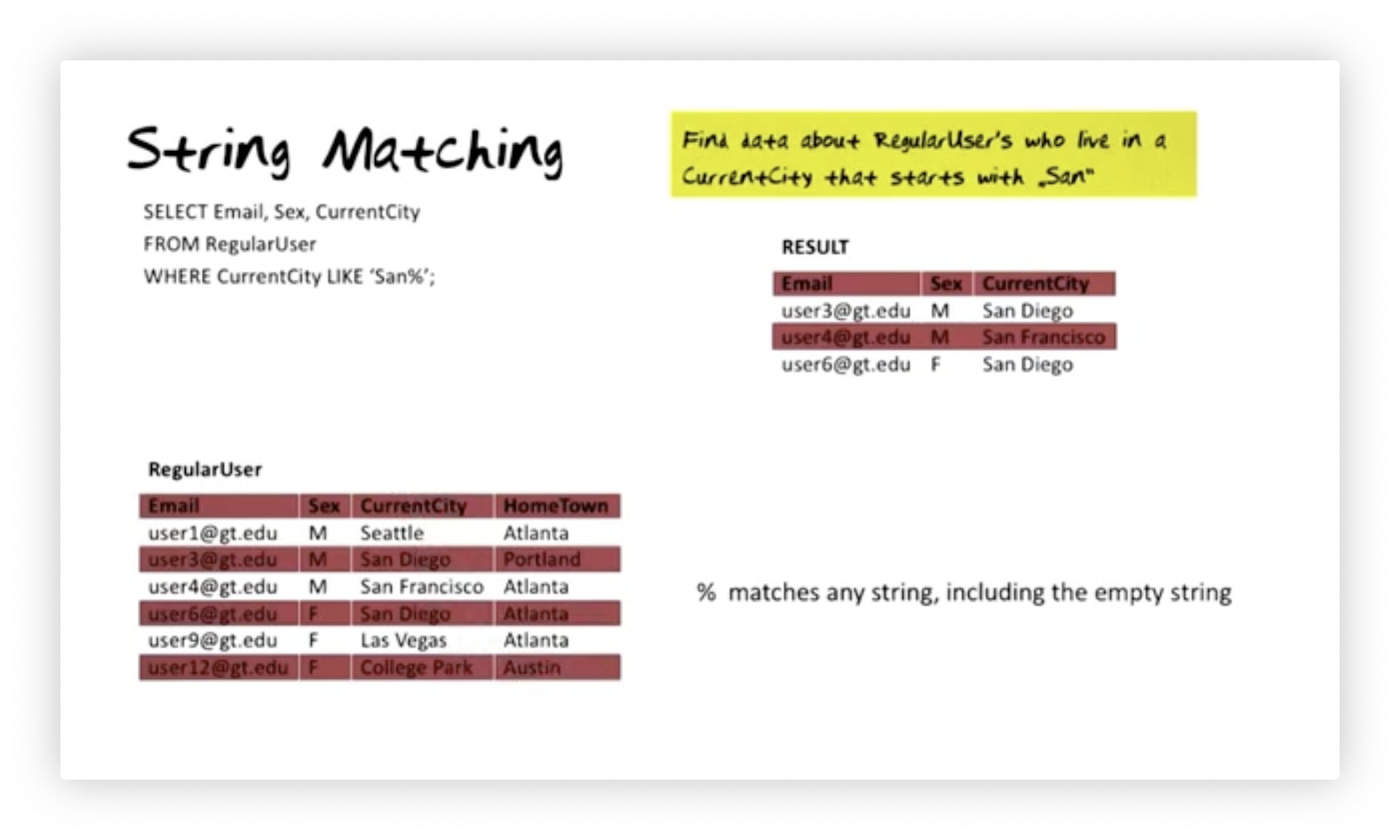

String Matching

Until now, most of the SQL queries we have looked at have been SQL versions of

relational algebra queries (except DISTINCT). However, SQL databases are

practical tools and, therefore, must have capabilities outside the scope of

abstract relational algebra and calculus.

The second practical operation we examine is string matching. Suppose we want to find information about regular users who currently live in a city that starts with "San". We can express that query as such:

SELECT Email, Sex, CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

WHERE CurrentCity LIKE 'San%';The percent sign, '%', above matches any string, including the empty string. For example, 'San%' matches the literal string 'San' and 'San' plus any number of subsequent characters. Let's look at the result, which includes regular users living in San Diego and San Francisco.

There are more types of wildcards in string matching. Whereas '%' matches zero or more characters, the '_' character matches exactly one character. For example, we can select regular users who currently live in cities that have precisely six characters where the first letter is "A" with this query:

SELECT Email, Sex, CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

WHERE CurrentCity LIKE 'A_____';Using the image above, we can see that the result of this query will only include the regular user who currently lives in Austin.

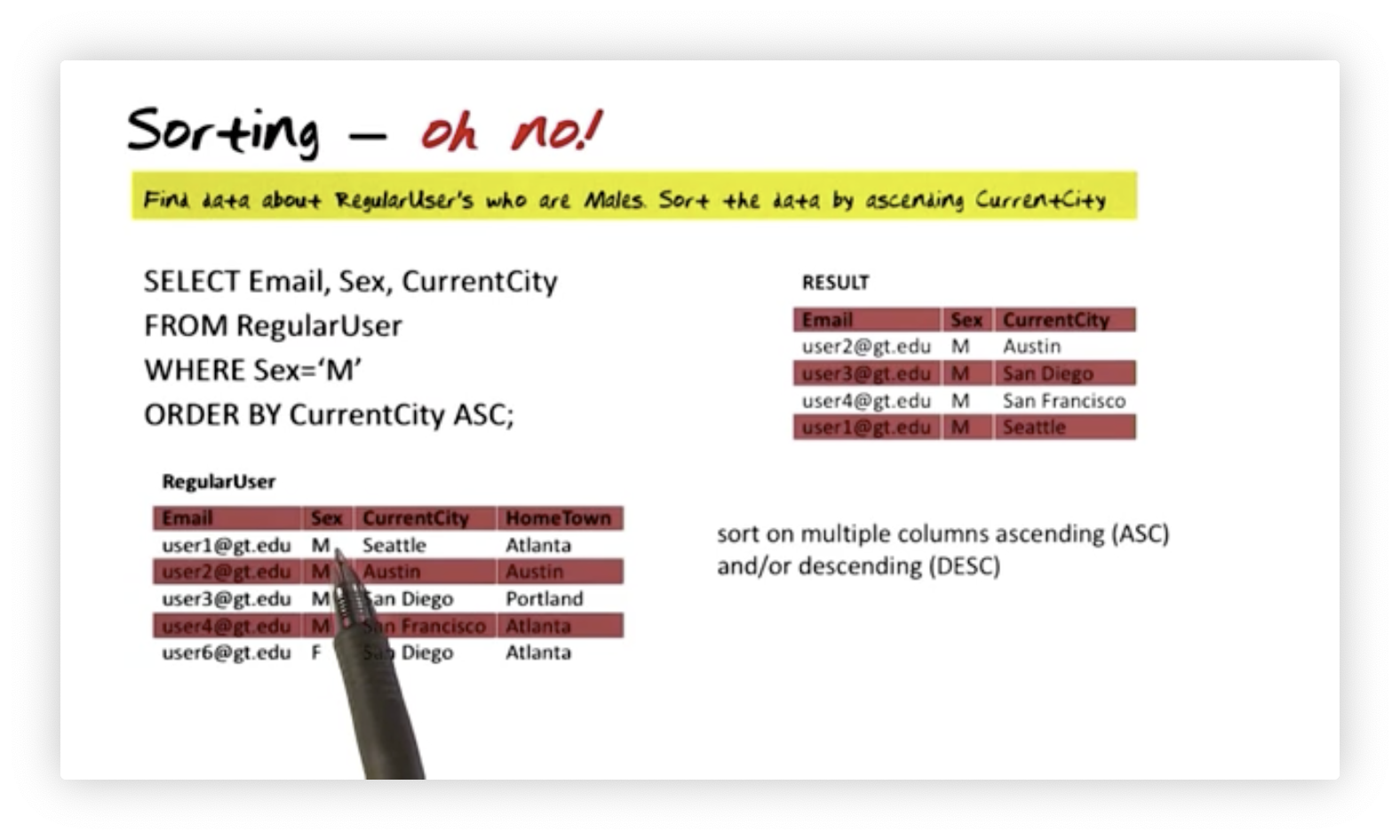

Sorting

Sorting is another practical concern that does not have roots in algebra or calculus. Suppose we want to find data about regular male users and need that information sorted by current city. We can express that query as follows:

SELECT Email, Sex, CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

WHERE Sex='M'

ORDER BY CurrentCity ASC;

It is possible to sort on multiple columns, and we can specify the sort

direction as ascending, ASC, or descending, DESC, for each column we sort.

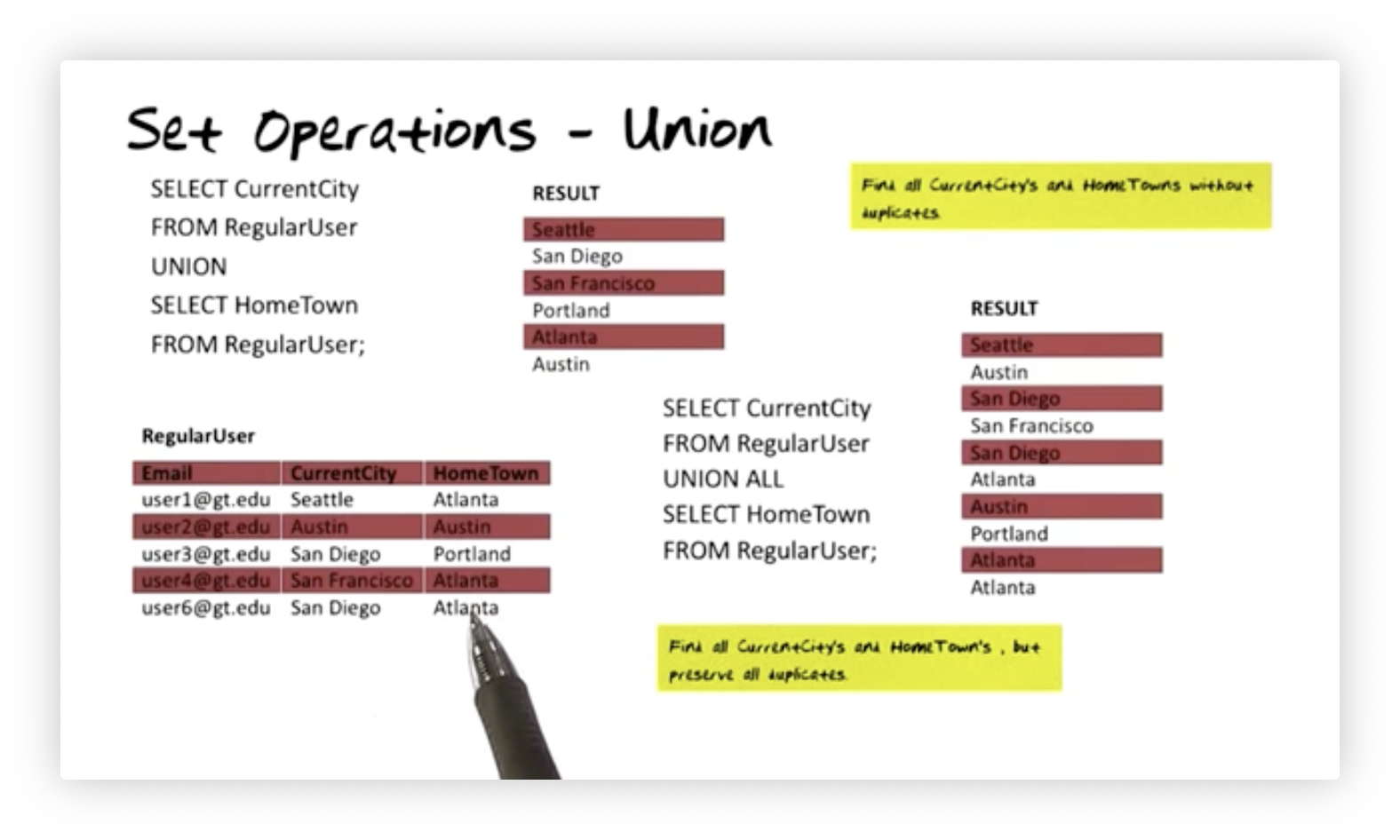

Set Operations - Union

Suppose we want to find all current cities and hometowns (without duplicates)

from the RegularUser table. We form two queries - one that selects all current

cities and one that selects all home towns - and then we find their set union

using the UNION operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

UNION

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;Whereas SQL queries generally may return duplicates, the union, intersection,

and set difference operators only return sets. If we want duplicates in our

result, we would instead reach for the UNION ALL operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

UNION ALL

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;

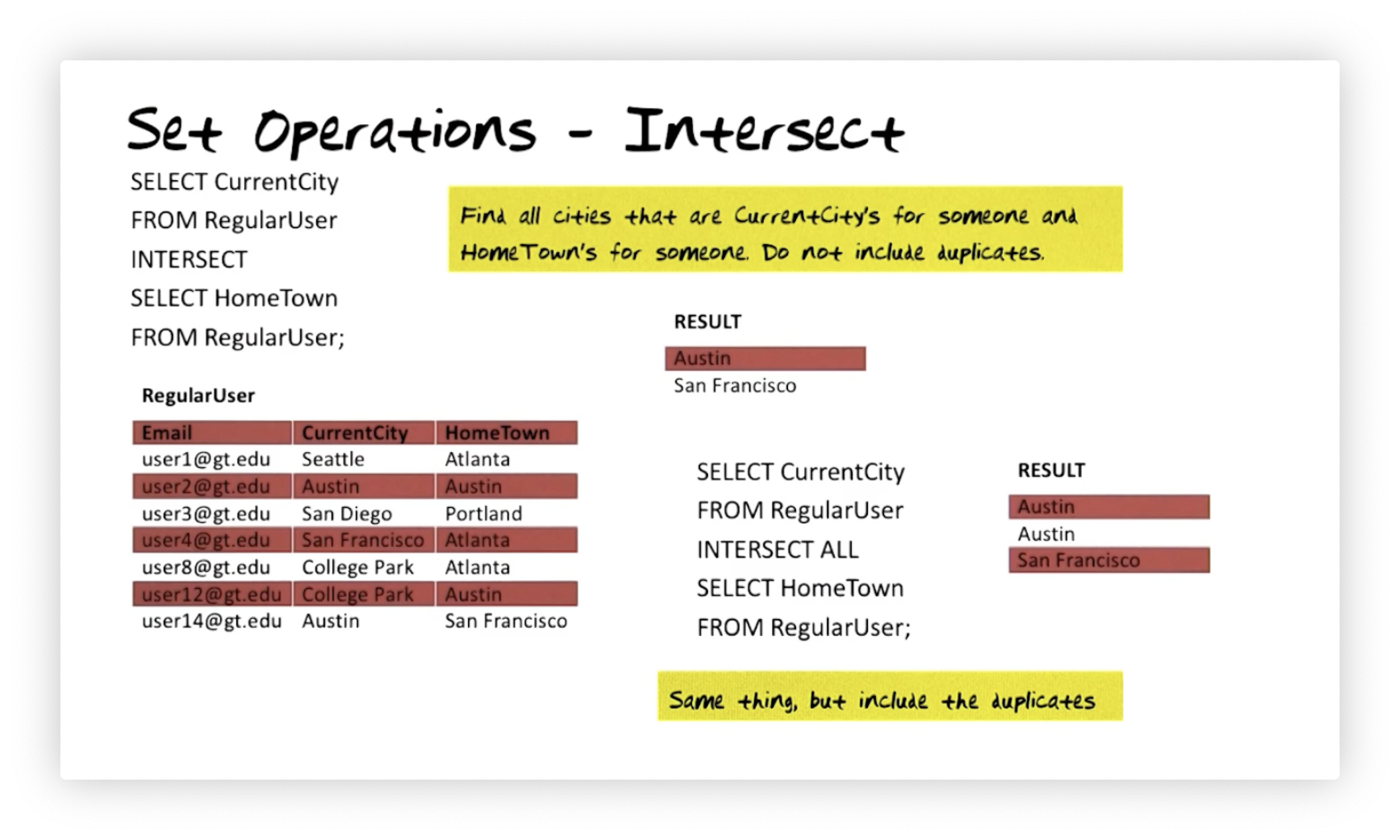

Set Operations - Intersection

Suppose we want to find all cities that are someone's current city and

someone's hometown without including any duplicates. We form two queries - one

that selects all current cities and one that selects all home towns - and then

we find their set intersection using the INTERSECT operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

INTERSECT

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;As we saw with the UNION operator, the INTERSECT operator removes duplicates

from the resulting table. If we want duplicates in our result, we would instead

reach for the INTERSECT ALL operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

INTERSECT ALL

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;

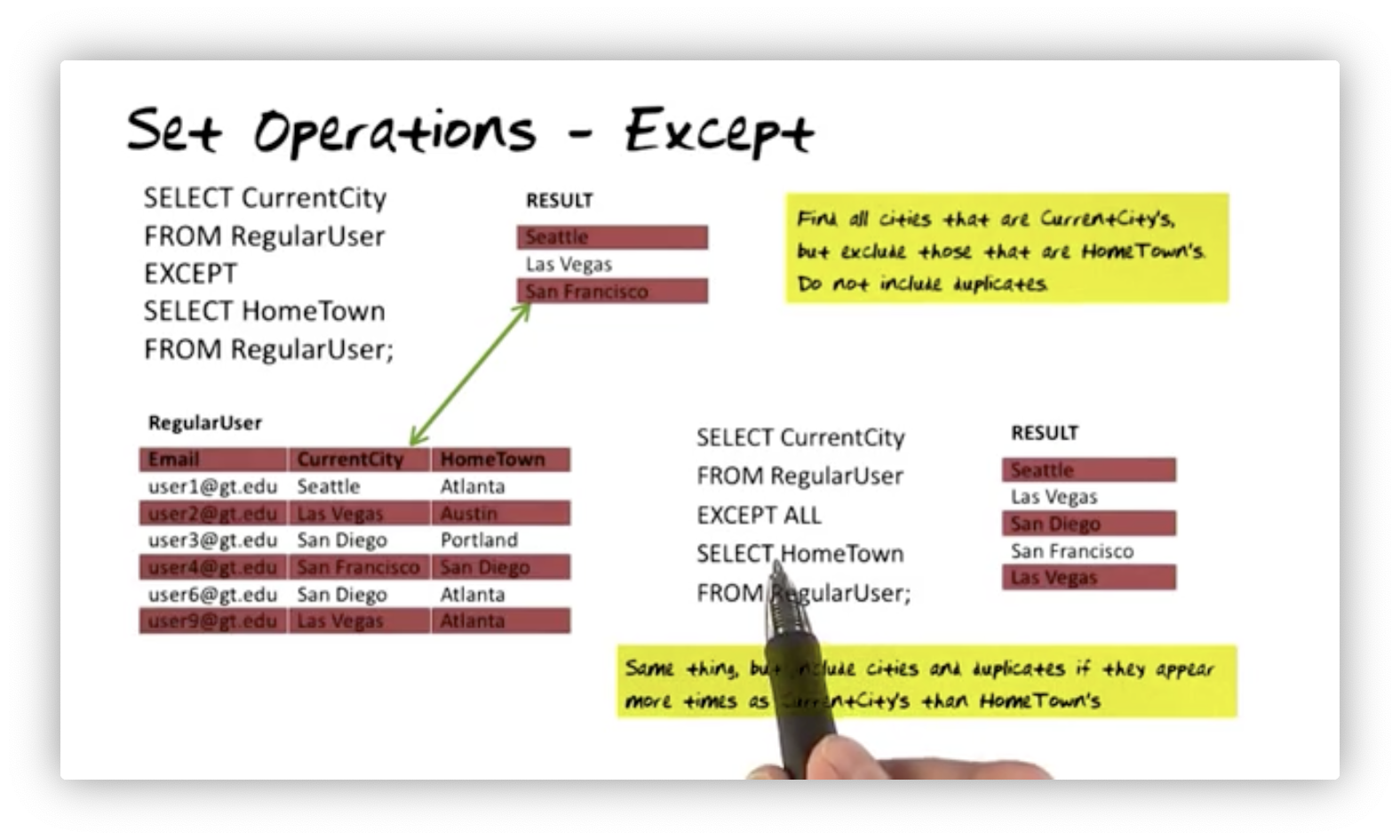

Set Operations - Except

Suppose we want to find all cities that are someone's current city but not

someone's hometown without including duplicates. We form two queries - one that

selects all current cities and one that selects all home towns - and then we

find their set difference using the EXCEPT operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

EXCEPT

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;As we saw with the UNION and INTERSECT operators, the EXCEPT operator

removes duplicates from the resulting table. If we want duplicates in our

result, we would instead reach for the EXCEPT ALL operator:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser

EXCEPT ALL

SELECT HomeTown

FROM RegularUser;

San Diego appears as a current city twice in RegularUser and a hometown once.

Notice that this city appears in the result of the query using EXCEPT ALL but

not the one using EXCEPT. Why? If we subtract a multiset with one occurrence

of a value from a multiset with two occurrences of a value, we end up with a

multiset with one occurrence of the value.

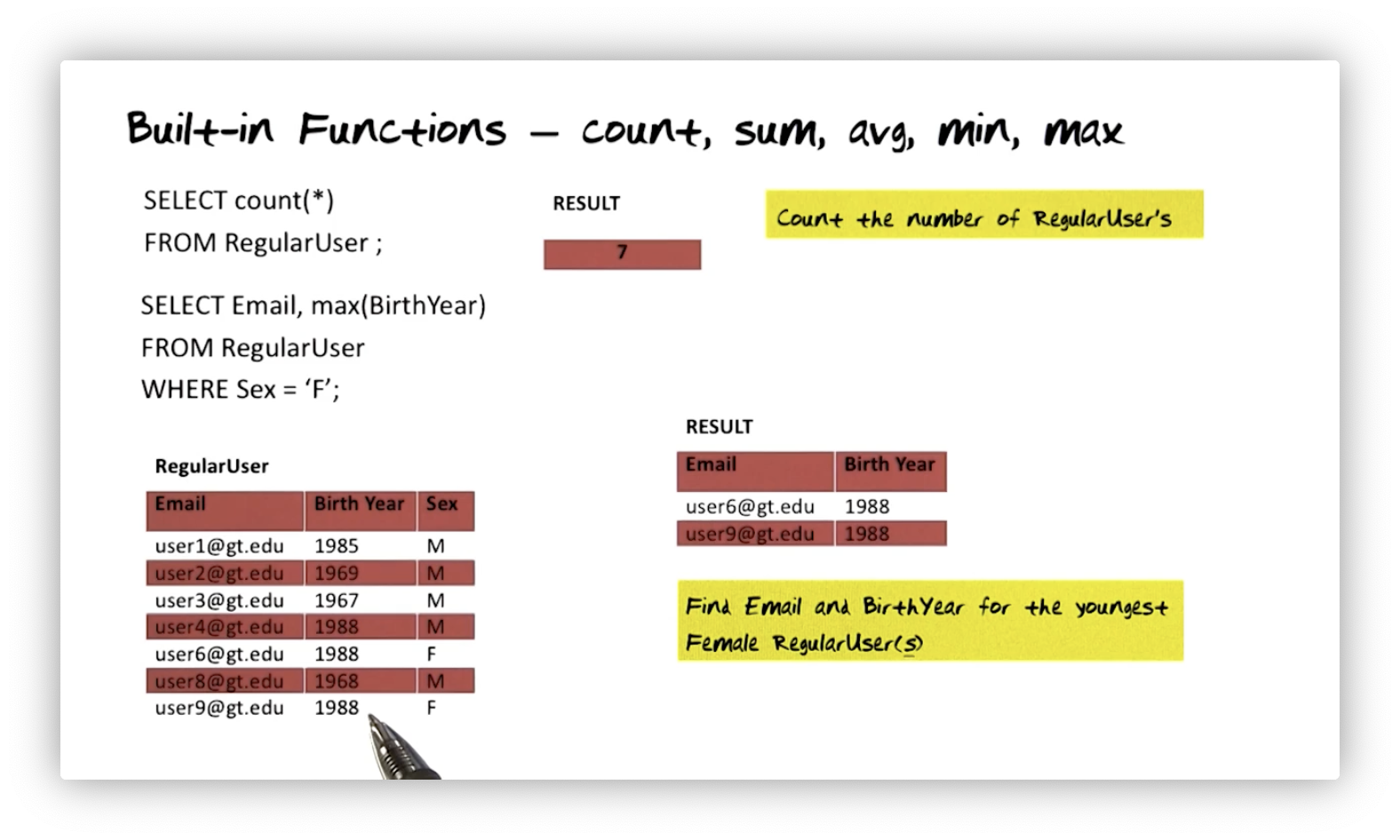

Built-in Functions

Continuing our discussion about practical functionality in commercial databases,

let's consider some built-in functions, such as count, sum, avg, min,

and max.

Suppose we want to count the number of regular users. We can use the count

built-in to retrieve the number of rows in RegularUser:

SELECT count(*)

FROM RegularUser;Suppose we want to select the email and birth year for the youngest female

regular user. Since the youngest users have the "largest" birth years, we can

use the max built-in like so:

SELECT Email, max(BirthYear)

FROM RegularUser

WHERE Sex = 'F';

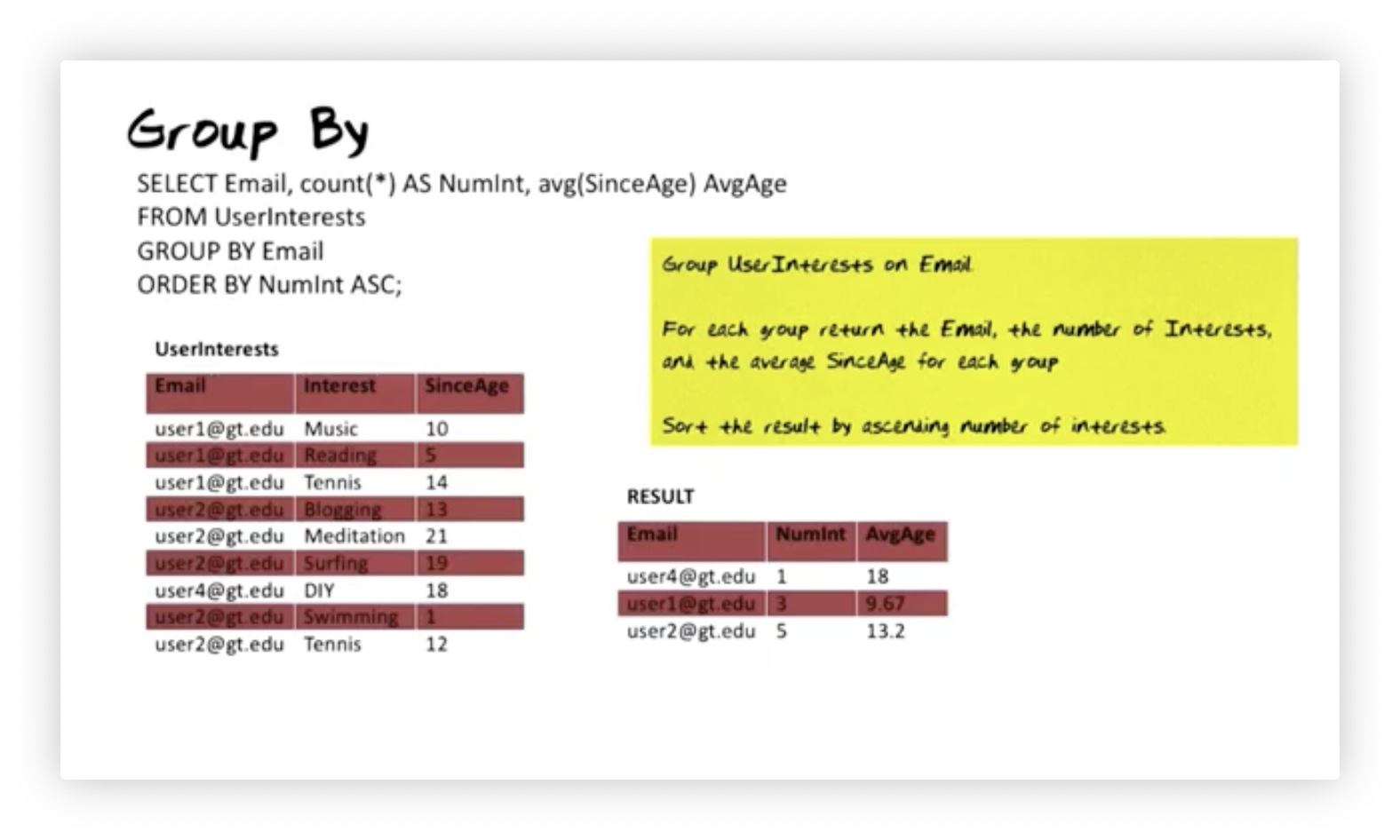

Group By

Sometimes, we want to group the data that comes back from a query and apply some simple calculations within each group. For example, suppose we wish to group user interests by user email. For each group, we want to return the corresponding email, the number of interests the user has, and the user's average "since age". Furthermore, we want to sort the result by the number of interests ascending. Here's that query:

SELECT Email, count(*) AS NumInt, avg(SinceAge) AvgAge

FROM UserInterests

GROUP BY Email

ORDER BY NumInt ASC;

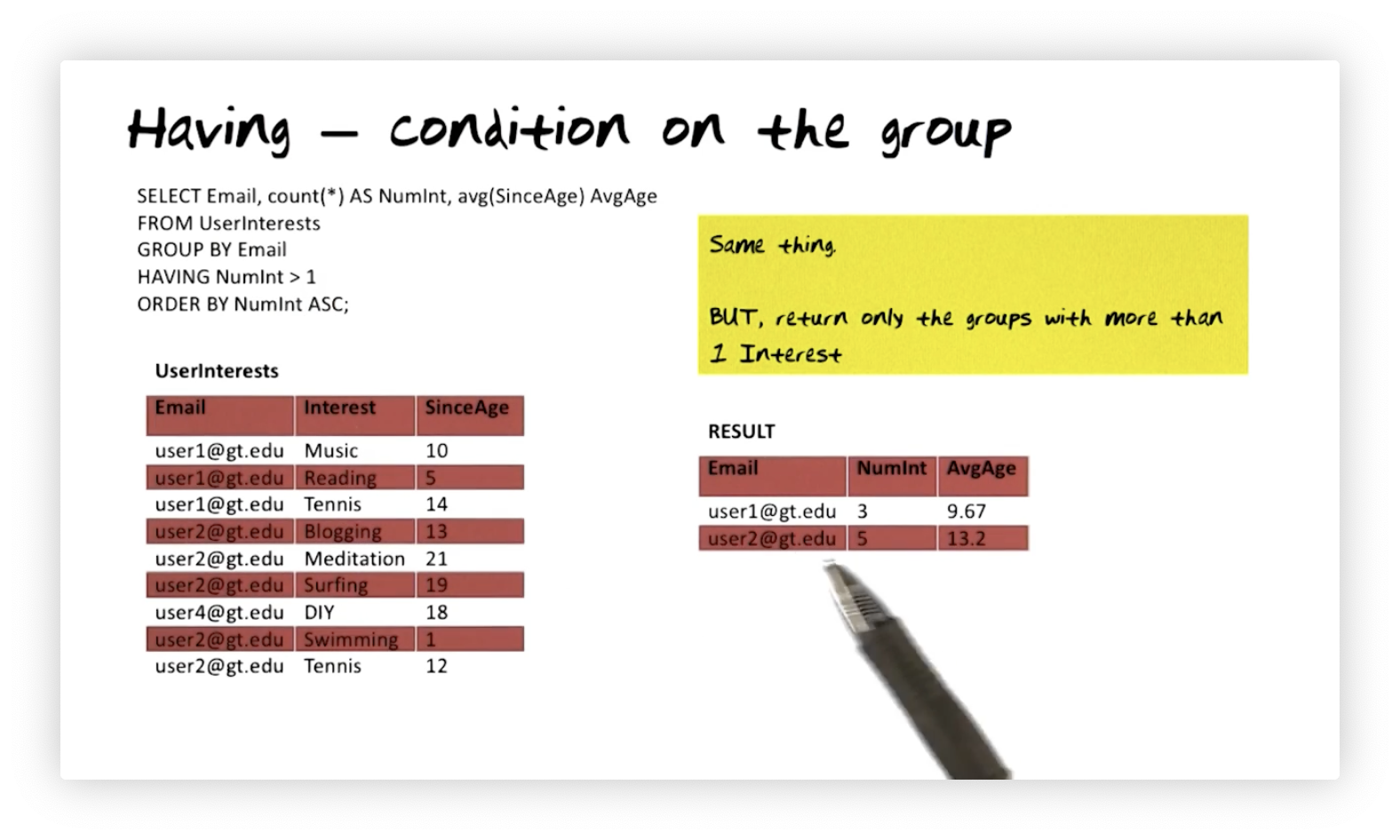

Having - Condition on the Group

Suppose we want to group user interests by user email. For each group, we want

to return the corresponding email, the number of interests the user has, and the

user's average "since age". Furthermore, we want to sort the result by the

number of interests ascending. This time, we want only to return the groups with

more than one interest. We can accomplish this with a HAVING clause:

SELECT Email, count(*) AS NumInt, avg(SinceAge) AvgAge

FROM UserInterests

GROUP BY Email

HAVING NumInt > 1

ORDER BY NumInt ASC;

Notice that user four is absent from this query since they only have one interest.

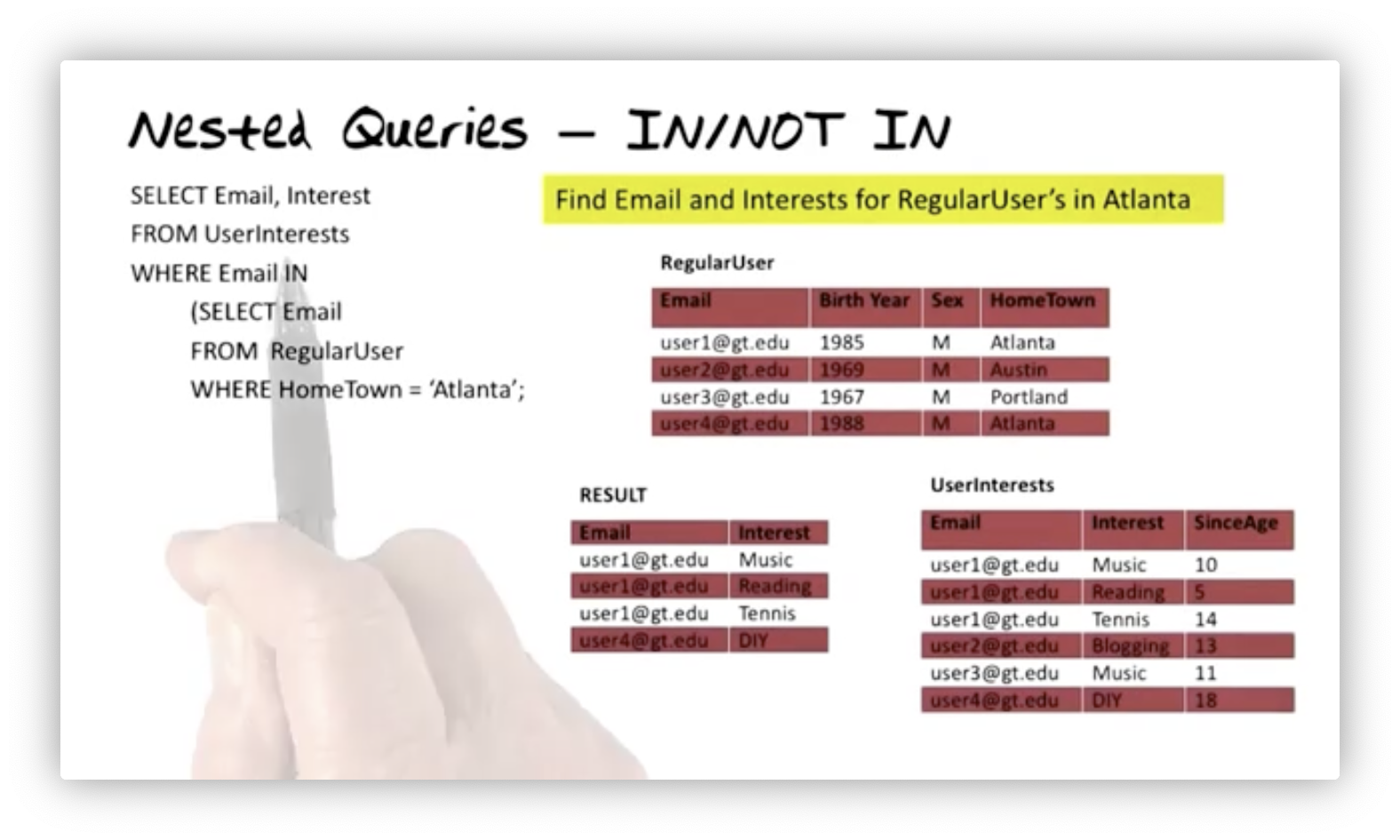

Nested Queries - IN/NOT IN

The final SQL concept we will explore is nested queries. Let's start by retrieving the email and interests of all regular users in Atlanta.

SELECT Email, Interest

FROM UserInterests

WHERE Email IN (

SELECT Email

FROM RegularUser

WHERE HomeTown = 'Atlanta'

);

We can envision this query in two ways. We can start with UserInterests and

see if the email for each row is associated with a regular user who lives in

Atlanta. Alternatively, we can start with RegularUser, retrieve the email of

all users in Atlanta, and then find the interests for those emails from

UserInterests. We say there is no correlation between the tuples considered in

the outer and inner queries; in other words, the inner query returns the same

result regardless of the outer query.

An alternative way to express this query without nested queries is by joining

UserInterests on RegularUser and selecting the appropriate rows:

SELECT U.Email, Interest

FROM UserInterests I, RegularUser U

WHERE I.Email = U.Email AND

HomeTown = 'Atlanta';Nested Queries - Comparisons, SOME/ALL

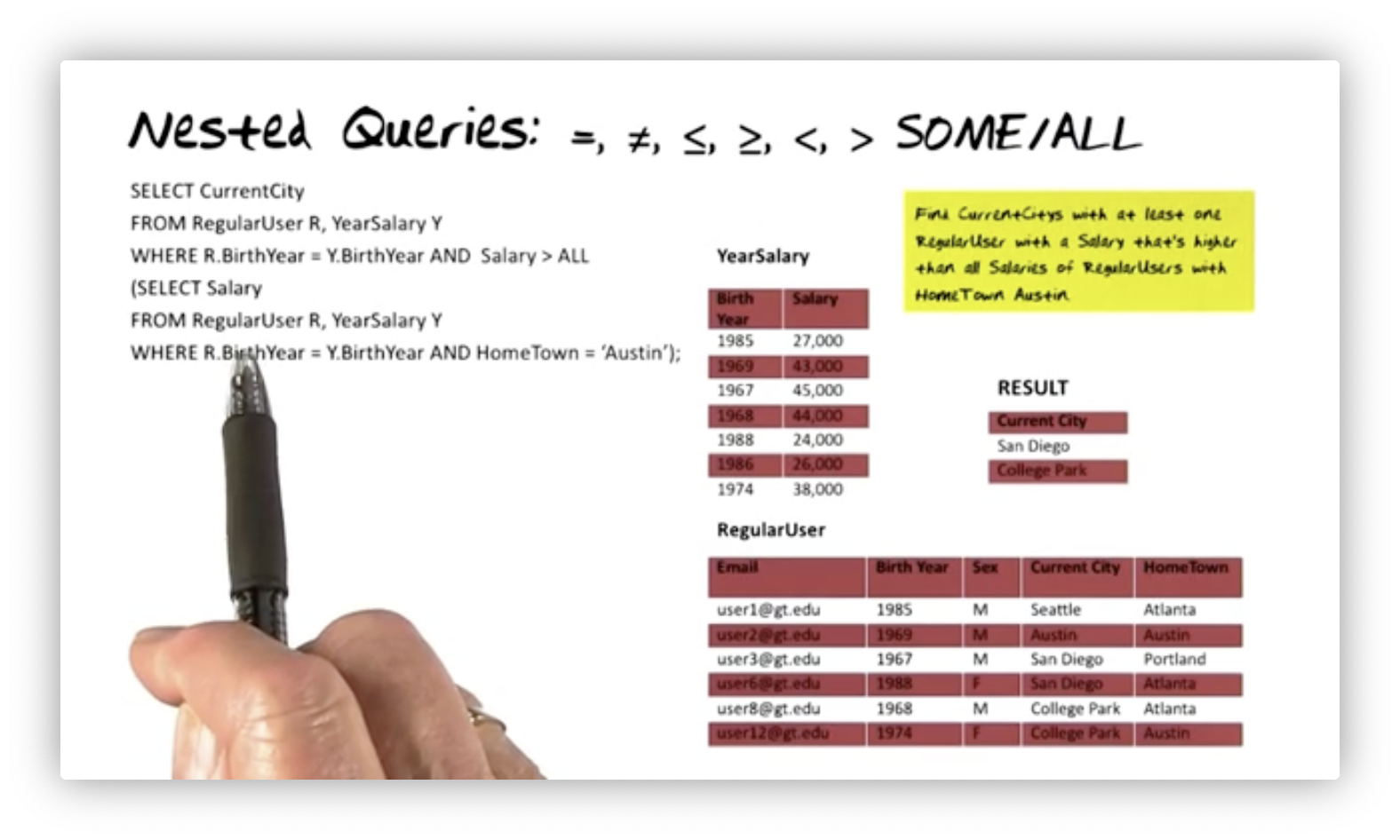

Let's find current cities with at least one regular user with a salary higher than all salaries of regular users from Austin.

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser R, YearSalary Y

WHERE R.BirthYear = Y.BirthYear AND Salary > ALL

(SELECT Salary

FROM RegularUser R, YearSalary Y

WHERE R.BirthYear = Y.BirthYear AND HomeTown = 'Austin'

)

Let's focus on the inner query first. Since the Salary and HomeTown columns

are not in the same table, we must first join YearSalary and RegularUser.

Next, we select the rows where HomeTown is Austin and the birth years are

equal. Finally, we project the result of the join and selection onto Salary,

leaving us with the salaries from regular users who live in Austin.

Let's now turn to the outer query. Again, we must join YearSalary and

RegularUser since we need both CurrentCity and Salary information. Which

rows do we select? We only want the rows where the birth years are equal, and

the Salary is greater than all the values of the inner query - namely, the

salaries of individuals from Austin. Finally, we project that selection onto

CurrentCity, and we have our final answer.

Notice that we don't actually need to ensure that each considered salary is greater than all the salaries of users from Austin; we only need to ensure that it's greater than the maximum of those salaries. Consider this alternative query:

SELECT CurrentCity

FROM RegularUser R, YearSalary Y

WHERE R.BirthYear = Y.BirthYear AND Salary >

(SELECT max(Salary)

FROM RegularUser R, YearSalary Y

WHERE R.BirthYear = Y.BirthYear AND HomeTown = 'Austin'

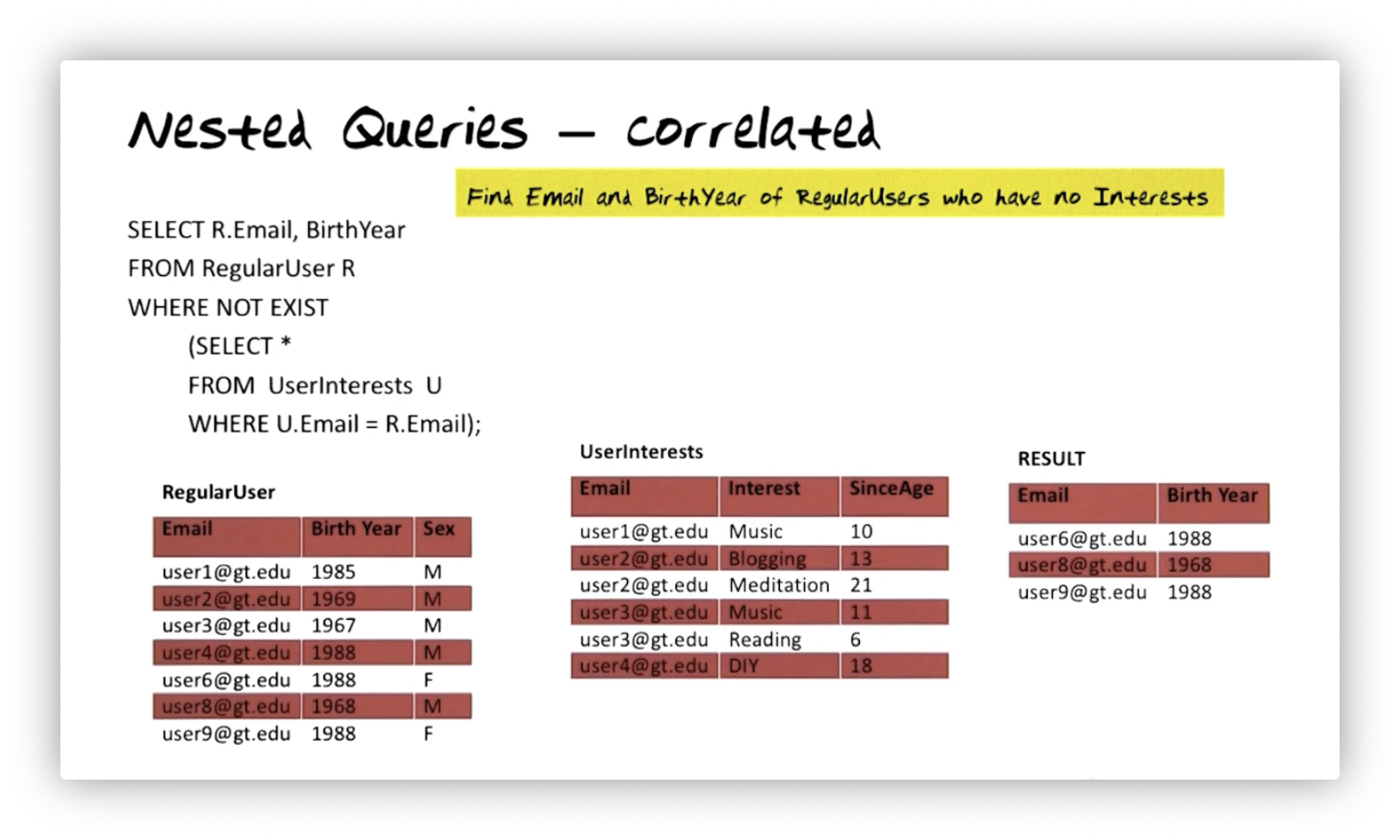

)Nested Queries - Correlated

The last type of nested query we will examine is correlated queries. Suppose we want to find the email and birth year of regular users who have no interests:

SELECT R.Email, BirthYear

FROM RegularUser R

WHERE NOT EXIST

(SELECT *

FROM UserInterests U

WHERE U.Email = R.Email)

In the inner query, we select everything from UserInterests where the email

associated with the interest equals the email of the regular user row being

considered. Notice that the variable R is not defined in the inner query; this

is known as a reference out of scope. The outer query defines R, and the

inner query holds a reference to this query. As a result, we cannot evaluate the

inner query without the outer query; the two are correlated.

We can picture this inner query being evaluated once for each row in the outer

query. For example, consider the first row in RegularUser. To determine if we

can include the Email and BirthYear from that row, we must first execute the

inner query on UserInterests and determine if that user has any associated

interests. Since they do - music and blogging - that user is not included in the

result.

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy